The march of the invisibles

Domestic workers all over the world are campaigning for recognition as regular employees. Their voice is coming stronger, thanks to global networking between activists, NGOs and researchers.

Domestic workers are at the centre of the global transformation that is currently turning the world of work upside down. The more the welfare state is rolled back, the more urgently people are needed to look after the young, the elderly and the infirm. Domestic workers are the original gig workers, hidden in the houses. They were around long before the advent of digital precarious employment and they have already spent many years fighting against their invisibility and lack of rights. During the pandemie of Covid 19 they were among the worst-hit categories concerning work and private life. But nevertheless they could record some important victories in the last ten years.

The movement received a boost in 2011, when the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted Convention No. 189 recognising domestic workers as regular employees. A number of domestic workers were involved in the negotiations. One year later, they formed the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) which now has more than 590,000 members in 63 countries. The majority of them are organised in associations, cooperatives and trade unions. Their President is Myrtle Witbooi, a south african activist and former “housemaid”. “But in 1967 I discovered my talent to speak and to represant other persons that can’t do it for themselves and since then I never stopped”, she says.

A FORUM FOR WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD

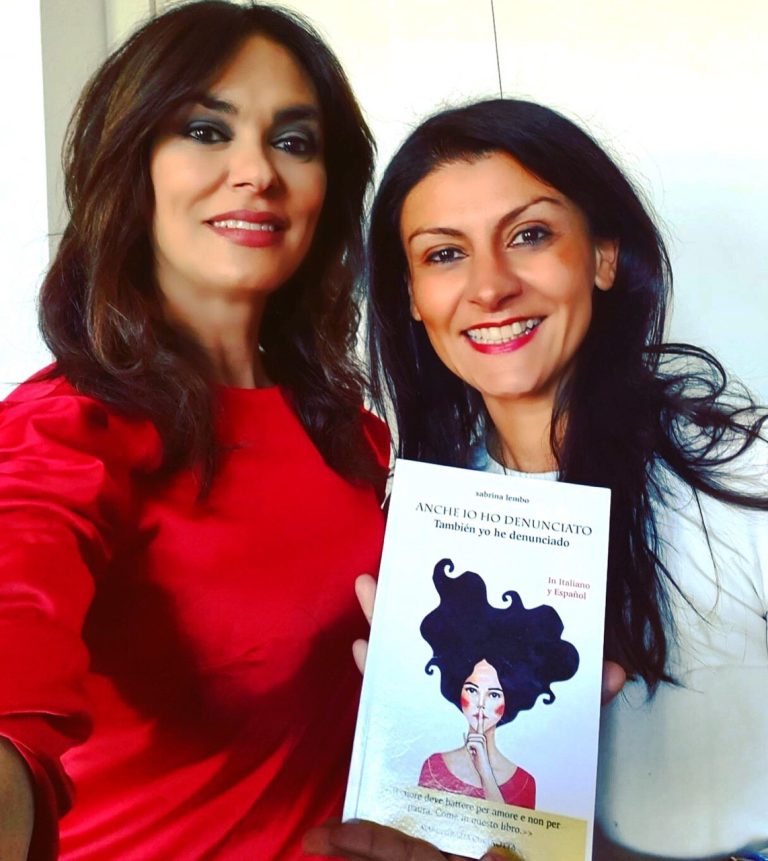

“It is a widespread misconception that domestic workers cannot be organised”, explains Sabrina Marchetti. She coordinated the European research programme DomEqual and is Associate Professor in Sociology at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. The project is terminated last year but the meetings organized by Marchetti and her team provided the women and their organisations all around the world with an important forum that still is working. For many domestic workers, life is a hell – not only in the villas of the super rich everywhere from Monte Carlo to Mexico, but also in the dismal homes of elderly people in Europe, where they often provide round-the-clock care for paltry wages. They are like invisible helpers who keep the household running. They clean, cook, bring up other people’s children and care for other people’s parents while their own families are often thousands of miles away.

“It is a widespread misconception that domestic workers cannot be organised”, explains Sabrina Marchetti. She coordinated the European research programme DomEqual and is Associate Professor in Sociology at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. The project is terminated last year but the meetings organized by Marchetti and her team provided the women and their organisations all around the world with an important forum that still is working. For many domestic workers, life is a hell – not only in the villas of the super rich everywhere from Monte Carlo to Mexico, but also in the dismal homes of elderly people in Europe, where they often provide round-the-clock care for paltry wages. They are like invisible helpers who keep the household running. They clean, cook, bring up other people’s children and care for other people’s parents while their own families are often thousands of miles away.

The ILO estimates that more than 75 million people worldwide earn their living as domestic workers, 76,2 per cent are women. And every single one of them has a story to tell. American Ai-jen Poo has heard hundreds. She has been campaigning for domestic workers ever since 25 years. “As student I was struck by the silent army of non-white women wheeling children through Manhattan who obviously weren’t their own”, she says. In spite of their excessively long working hours and the fear of reprisals, more and more women started attending meetings of small groups, ultimately resulting in the emergence of a community. In 2007, these groups successfully established the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA).

For Ai-jen Poo, this was a huge victory. “We are the only people in the USA who organise poor female workers”, she explains. Poo firmly believes that in the future everyone who finds themselves in the new, precarious world of work will benefit from their struggles. “The struggle is about us, but it’s also about the future of work and the employment relationships all over the world”, she says.

Michaela Namuth